Rathbones' Paying for care in later life

24 November 2021

What changes to state funding of care mean for you

Many people who have worked hard all their lives and paid National Insurance Contributions feel resentment that the state has been unwilling to pick up the tab for necessary care costs in their final years. The result is hefty monthly bills that can bite hungrily into any inheritance they planned for loved ones. As we live longer on average, more of us are finding ourselves in need of later life care, but who should pay for it?

An independent commission in 2011 estimated that around one in ten adults aged 65 face lifetime care costs of more than £100,000. A decade on and with costs having risen, the government estimates that figure is now one in seven.

Many of us not yet at this stage of life ask how to plan sensibly for such an unpredictable and potentially costly scenario.

A succession of governments has failed to address the problem. But that appears to have changed. In September the UK parliament passed a new funding plan for health and social care in England, “Build Back Better”.

It sets out details for a ringfenced UK-wide Health and Social Care Levy to be introduced in April 2022 and funded initially by a 1.25% increase in National Insurance Contributions and dividend tax rates, and a separate tax on earned income from 2023.

So much for the pain. What about the benefits? From October 2023 no eligible person starting care in England will be forced to spend more than £86,000 over their lifetime on the cost of their care.

Anyone with assets of less than £20,000 will not have to make any contribution for their care from their savings or the value of their home. However, people may still need to make a contribution towards care costs from income. Those with less than £100,000 will be subsidised — you can expect to pay no more than 20% of costs.

How does that compare with today?

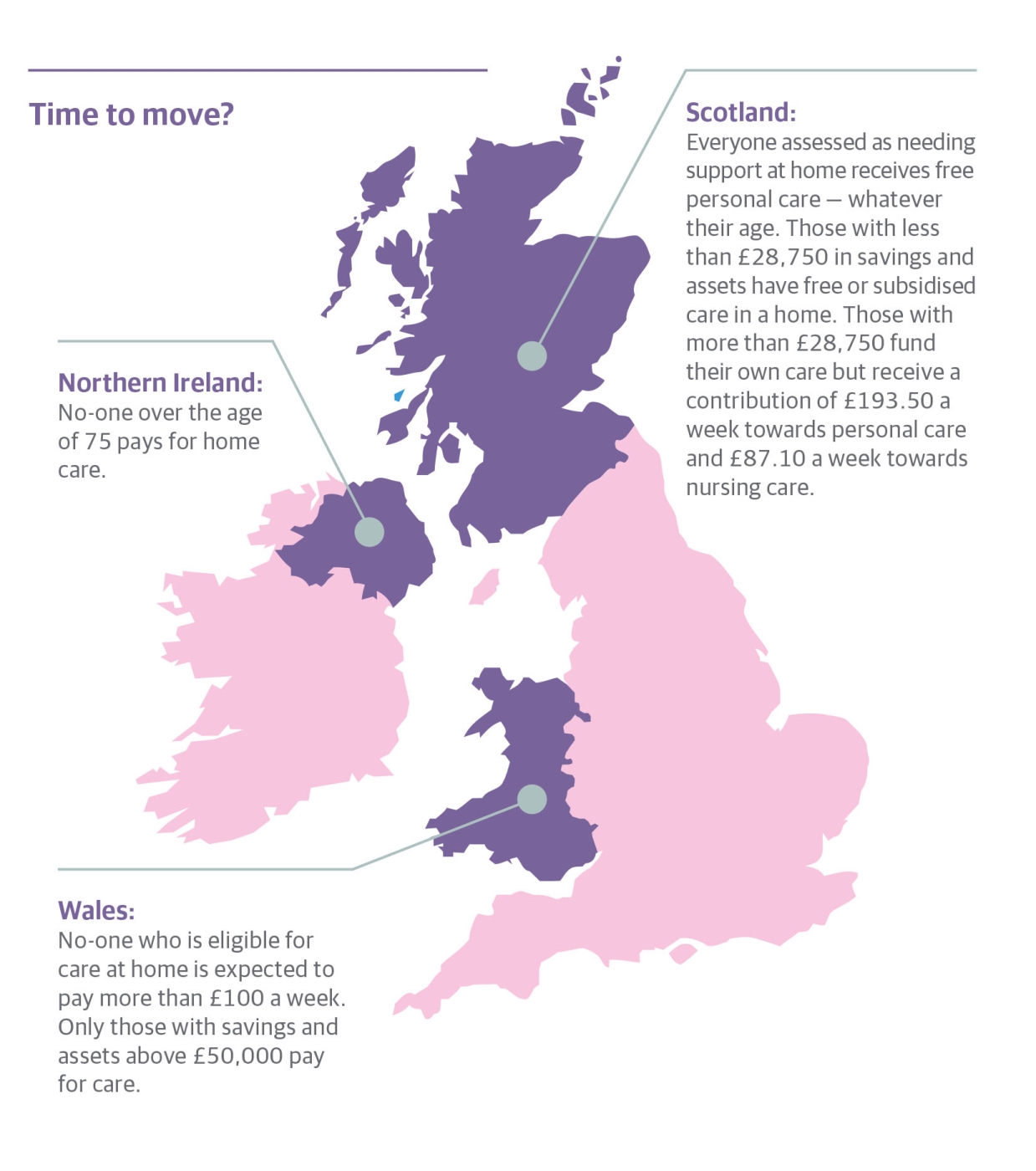

At the moment there is a £23,250 capital means test ceiling above which all care costs must be met by the individual in England and Northern Ireland (see below for an illustration of how matters differ across the UK).

“At the moment there is a £23,250 capital means test ceiling above which all care costs must be met by the individual.”

Below these levels you may still be asked to pay a contribution towards costs. The value of an individual’s home is generally included in any capital means test unless it continues to be occupied by a dependant, partner or relative aged at least 60.

This, essentially, is the self-funding route and means the limit on what you pay may be the bulk of your wealth.

The small print

On the face of it, therefore, the reforms are to be warmly welcomed and could make a big difference to many clients, helping protect their lifetimes savings. Indeed, the headline details might encourage some to release cash they had ringfenced for potential later life care needs to give to loved ones now, perhaps with the aim of reducing inheritance tax liabilities.

But as we warned at the start, it pays to read the small print. There are some caveats. Serious ones.

— Daily living vs. daily tasks

Not all care costs will count towards the £86,000 cap – only those associated with performing daily tasks, such as washing, dressing and eating, whether that is in a care home or a person’s own home.

When receiving residential care, a portion of the care home fees will fund accommodation-related costs — those associated with daily living, like food, energy and building maintenance. These will not count towards the cap.

— What the government will pay

The government has not said how much it expects people to contribute for daily living costs. In 2014, when a similar scheme was mooted by the coalition government, it was suggested that people’s contribution to these accommodation costs should be fixed at £12,000 a year.

These costs could be significantly higher if a cap is not introduced, particularly so for care homes in affluent areas and/or looking to provide a superior service.

What to budget for |

— Deciding when you need care

Another potential issue is who decides when you need care towards performing daily tasks. This is assessed by local councils. Only the frailest person — those unable to perform daily tasks — will qualify. Some councils have more money than others. It is not too difficult to imagine that those with the least cash will be the most rigorous in their interpretation of this rule.

The BBC has reported that more than half of requests are currently declined. The County Councils Network predicts this will not change significantly under the new funding regime.

— Deciding where you go for that care

If the state is funding care, this may also complicate the decision as to where you — or a loved one — goes to receive that care. Suffice to say the range of facilities and quality of care can vary wildly from home to home and is often dependent on fees.

The Institute for Fiscal Studies has calculated that around 80% of the funding raised by the new plan will go to the NHS in the first two years, rather than on social care. While few would doubt the need of the NHS for this funding, there is a growing crisis in care homes.

A typical care home of 50 residents is reportedly seeing energy bills doubling from nearly £50,000 a year to £100,000. Wages are under pressure too, with many staff leaving the industry for better paid jobs elsewhere. This must surely feed through to fees.

It means that clients budgeting for later life care costs, far from reducing expectations, may need to raise them significantly.

If you are concerned about making provision for later life care and how the new regulations will affect you, please contact your Rathbones adviser, or get in touch with us.

Sign in to continue reading

Access all our articles and search the provider directory for free.